Make Way For The Monarch: Migration and Preparation

- Rebecca Cummings

- Oct 20, 2023

- 5 min read

Of all the California butterflies, the most well known is the Western Monarch butterfly. This butterfly, Danaus plexippus, is an orange butterfly with black vein outlining and white dots of varying sizes on the edges of the wings. With a wingspan of around four inches, the Monarch Butterfly is one of the larger species in Southern California. They have two migratory seasons, one in the fall and one in the spring.

During their overwintering season, the Western Monarch will migrate 620 miles to the California coast from their inland summer sites. “Overwintering” refers to the region chosen by the butterflies to shelter over the winter months. The coast provides a warm and dry climate to protect them from the season's rain and cold temperatures. The Eastern Monarchs migrate for the same reasons, but they journey up to 3,000 miles from Northern America and Southern Canada to the Oyamel Fir Forest in Central Mexico. For the Western Monarch specifically, the shorter migration distance means that sightings are more common year round across California.

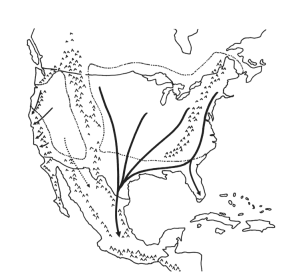

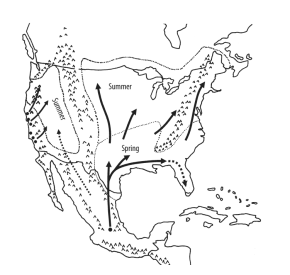

Photos of Western and Eastern Monarch Butterfly flight paths from Monarch Joint Venture showing directions of fall (left) vs spring (right) Monarch migrations

Starting in September, the butterflies leave the western Rockies and travel to the coast of California, where the butterflies find large groves of plants like eucalyptus trees to roost for the winter. They will cling to the trees to rest during the wet and rainy season, leaving during the day for sunning and to find food from nectaring flowers. The Western Monarch has far more overwintering sites than the Eastern Monarch which causes two main differences in the species’ overwintering behavior. First, the Eastern Monarch will have a much more densely populated roosting area, which causes entire trees to be engulfed by the insect. Second, the larger distance between roosting sites makes the western species more stable than the Eastern Monarch because if an environmental disaster were to wipe out a roosting site, less of the overall population would be lost.

Over the course of the year, there are around four generations of Monarchs that all serve different purposes. The most unique is the migratory generation. This generation begins in the late summer and they will live up to nine months, as opposed to the non-migratory generations that live for only four to six weeks. They also have a specific gene that differs from non-migratory generations that helps with flight efficiency and muscle function. This gene, Collagen IV alpha-1, increases metabolism ability during flight but has little impact on other characteristics between migrating and non-migrating generations. The migration of Monarch Butterflies is unique since the migrating generation has never previously been to their overwintering sites. Having been born right before migration season, they rely on their sun compass and magnetic compass to guide them. Monarchs will use their circadian rhythm, which is an internal 24 hour cycle, and the sun’s position along the horizon to keep a steady flight path to their overwintering sites. Many orders of insects are also suspected to be able to use earth’s magnetic fields to get a sense of direction. This magnetic field sensitivity is utilized on cloudy days when the sun compass might not be available.

Once they make their way to their overwintering sites, they enjoy the nectar from various native plants that bloom during the fall and winter. The nectar from these plants gives the butterflies sugar energy needed for flight and reproduction. Monarchs will sip nectar multiple times a day, but are able to go two to three days without the sugar if weather does not allow travel to the flowers.

In California, the Monarch Butterfly is listed as an insect of great conservation needs and is slated to be entered into the Endangered Species Act in 2024 if their population continues to decline. Since the year 2000, the Monarch Butterfly population has decreased around 90% from 200,000 to just around 30,000 in the year 2020. These numbers vary greatly year to year and depend on the environmental factors that took place the previous year. Seasons that are too hot or too cold could prove fatal for the Monarch Butterfly because these extremes limit access to food. Climate change related issues are an increasing worry for Monarch Butterflies and many other insects. The wetter winters could limit their ability to leave their roosting sites to search for food without water falling on their wings. The hotter summer temperatures may also affect the quality and quantity of the flowers they feed on since many could dry out.

The graph above shows the Xerces societies annual western monarch Thanksgiving count from 2022. There is a significantly smaller number of butterflies reported now vs. the nineties, despite increasing the number of sites monitored. An odd occurrence is the presence of less than 5,000 butterfly sightings in the years 2018 to 2020, even though the years before and after had sightings of around 200,000.

There are many organizations in place to help ensure that the Monarch Butterfly is well supplied with food and shelter. Live Monarch or Roger's Gardens have programs where native milkweed is made available for free or at very little cost, and also have more information about how, where, and when to plant milkweed. Native milkweeds and flowering nectar plants have been placed along the Monarchs’ flight path in hopes that they will never go too long without nutrients or rest. Milkweeds are a crucial part of the Monarch Butterfly life cycle. They will lay their eggs on the leaves of the plants; once hatched, the caterpillar will eat off the plant until they are ready for metamorphosis. Milkweed is the only plant that is a suitable host for the Monarch egg and caterpillar. If milkweed is not available, the female Monarchs will hold off laying eggs until milkweed can be found. Studies from Journey North have shown that eggs laid on plants other than milkweed are sparse, and will result in dead caterpillars. Planting milkweed too close to the coastline could disrupt the butterflies' reproductive cycles and cause them to mate and lay a new generation of eggs before their overwintering is complete. In the absence of milkweed, the butterflies stop mating and laying eggs all together, but if milkweed is present during their overwintering, their environmental cue for reproduction will return. Since genetics differ from generation to generation, this could mean that the gene for improved flight function wouldn’t overlap with the migratory season.

Want to help do your part to care for the Western Monarch butterfly? Here are some essential plants to add to gardens or window sills. Native milkweed, when planted over one mile from the coastline, provides space for laying eggs and food for caterpillars. Some examples of native milkweeds are california milkweed, woolypod milkweed, heartleaf milkweed, and narrowleaf milkweed. In addition to these beautiful plants, some nectaring flowers would also be beneficial to the garden. To best help the monarch butterflies, find a native nectar plant that flowers in the fall to winter. Butterflies will feed on nectaring plants all year round, but flowers nectaring during their overwintering in Southern California would be the best option. Golden brush, seaside fleabane, smooth beggartick, or western vervain are all good choices for native nectaring plants. For more information on the Monarch Butterfly and its flight patterns, keep an eye out for an upcoming video on our website and YouTube!

Sources: Monarch Joint Venture, Roger's Gardens, Xerces Society, U.S. Forest Service, The Monarch Corporation, Journey North.

Comments